7 Data Protection Lessons Learned in August

Because "Art never sleeps" (F.F. Coppola)

This summer, I went on a GDPR detox to study other regulations.

But from time to time I came across things I had to comment on — I just couldn’t help myself.

It happened to me several times:

With two stories that clearly distinguish between privacy and intimacy — something I usually explained using my best privacy anecdote: the one about Fraga in Cambados. Today, you’ve got it in both text and video.

With an episode of the always hilarious John Oliver ("Garbage in, garbage out").

With Cecilia Sopeña exercising her “right to be forgotten.”

With the Deldits ruling (“the principle of accuracy must be applied according to context”), a March case that landed on my desk this August.

With Ter Stegen and the processing of professional athletes’ health data.

Real life beats fiction.

Bonus Track: In the EU, Coldplay would’ve gotten a good slap on the wrist over the whole KissCam thing.

You're reading ZERO PARTY DATA. The newsletter about data, artificial intelligence, and law by Jorge García Herrero and Darío López Rincón.

In the spare time this newsletter leaves us, we like to solve tricky issues involving AI and personal data protection. If you have one of those, give us a little wave. Or contact us by email at jgh(at)jorgegarciaherrero.com

1.- Three stories, to distinguish Privacy and Personal Intimacy

I collect PRIVACY-ANECDOTES. I always have.

My favorites are those that allow you to explain complex ideas in a flash—and make them unforgettable for the listener.

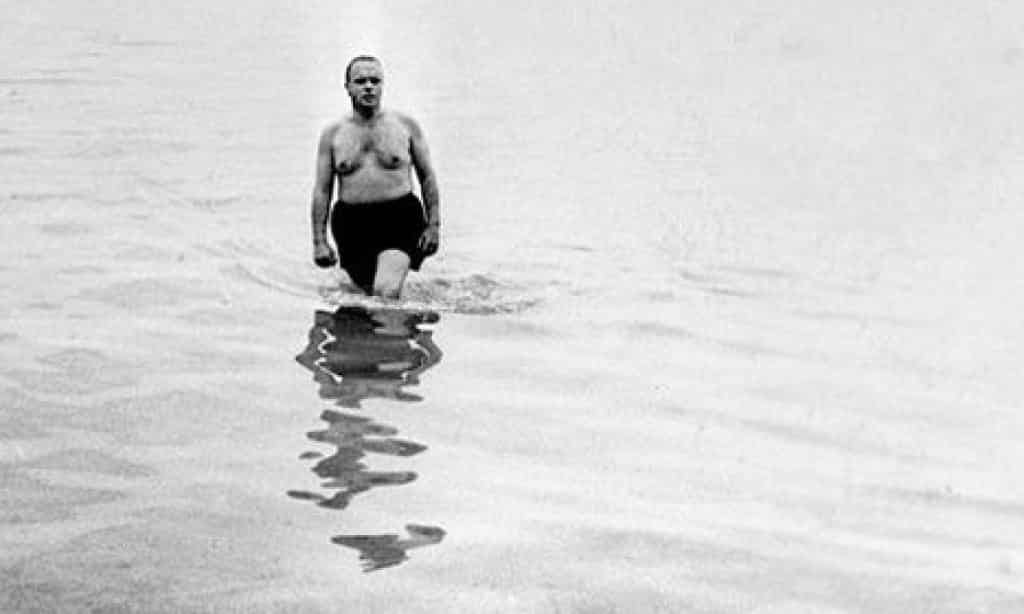

For years I’ve leaned heavily on the story of Manuel Fraga naked to explain, in one minute, the difference between the rights of “personal data protection” and “personal and family intimacy,” which sounds simple but is elusive for the explainer and very uninteresting for the listener.

But this summer, by one of those ironic twists of fate, I came across TWO OTHERS —almost— just as good. Almost, because it’s impossible to top that one.

a.) AI can protect your intimacy while destroying your privacy. How does that work?

The first one comes from this comment by Ethan Mollick.

He was talking about the (ahem, theoretical) benefits of a fairly exotic LLM use case: blind individuals who, to understand the contents of confidential documents without (ahem, theoretically) intermediaries, take pictures of them with their phones and ask a trusted AI assistant to summarize the contents.

A blind person who, instead of relying on a trusted family member or caregiver, shows a confidential document to ChatGPT to understand it is protecting their intimacy from their caregivers (something anyone can understand), but not their privacy: once the document is revealed to OpenAI, their data is no longer only in the best hands—their own.

Unless (obviously) they use a local LLM.

b.) Will electronic peepholes be the new CCTV cameras?

Complaints about video surveillance made up 19% of the total according to the latest report from the AEPD.

Pretty much everyone in the privacy world is shocked by a harsh reality: people casually share vacation photos, hookups, their minor children, physical or mental health issues, financial problems, etc. without much thought—yet do absolutely nothing when their data is blatantly misused (this is often called the "privacy paradox").

But if their neighbor or the city council installs a camera pointing anywhere close to their window… boom, formal complaint.

That's why I don’t find this news trivial: the Supreme Court ruling ordering the removal of one of those damned “electronic peepholes” and awarding damages to the people living across the hall… for violation of their right to intimacy. This came after the Spanish Data Protection Agency – AEPD—in a previous resolution—declared that there was no privacy issue “because it only captured what the neighbor could already see”.

c.) The Fraga story:

This is my favorite anecdote and I’ve told it a million times. I once told it in front of the then Head of the Legal Office of the AEPD and we all cracked up. As it should be.

You can see it in the video exactly from this point:

Or read it below:

A very young Manuel Fraga was inaugurating some event with Pío Cabanillas in Galicia on an infernally hot day. They decided to go to a little-known, discreet cove to cool off.

Cool off and much more, because they hadn’t brought swimsuits.

So there they were, “flailing around like sperm whales” when a bus full of schoolgirls chaperoned by nuns arrived—likely with swimsuits—intent on the same activity.

Upon seeing the girls approach, Fraga dashed out of the water toward the rocks where he’d left his clothes, covering his private parts with his hands. But Cabanillas, still in the water, yelled out a timeless privacy lesson:

"The face, Manolo, the face!! Cover your face—no one will recognize you by your balls"

Legal context: Fraga could choose to protect his right to intimacy by covering his genitals with his hands, or his right to data protection by covering his face.

Thus preventing the nuns and schoolgirls from associating the bold naked swimmer with the young Minister of Information and Tourism.

In other words, controlling the flow of his personal data to third parties.

2.- Cecilia Sopeña: right to be forgotten and data erasure in contract cases.

Cecilia Sopeña became famous as a content creator (math teacher and cyclist) and from there, jumped to OnlyFans where she began selling content typical of that platform.

The news is that this summer she decided to exercise her “right to be forgotten”:

That is, in her own words, “the right to delete from the internet everything that no longer reflects who I am or how I want to be remembered.”

Several problems arise here (and that’s the August lesson):

1.- What’s popularly known as the “right to be forgotten” actually refers to demanding search engines to de-index links—so that the engine doesn’t return them in search results—related to specific information (which remains intact on its original websites: usually online newspapers or similar) because the info is inaccurate, outdated, or irrelevant.

2.- Then there's the actual right of erasure. Broadly speaking (without going into too much detail), this allows any data subject to demand the deletion of personal data processed based on consent or a contract.

3.- The crux of this matter is that, when a contract is involved (as in Sopeña’s case, whose content was governed by (i) the contract with OnlyFans and (ii) the contract between OnlyFans and her “Fans”), no erasure can occur until the contract ends or is terminated. And termination will undoubtedly involve compensation.

Even more so if retroactive effects are intended.

So, aside from the obvious issue of trying to delete content released online—since anyone could have downloaded it and re-uploaded it across countless sites in a classic game of cat and mouse—there’s another, less obvious one: the compensation owed to the other party who profited from that content.

Profits that were essentially the price for something you gave up and now want to take back.

Somehow. So to speak.

And remember: set aside any heuristics or moral judgments when legally evaluating a case involving fundamental rights. They’ll only lead you astray.

3.- "Garbage in, garbage out" by John Oliver.

"Garbage in, garbage out" is an important concept in the world of datasets: if the data you use to train your AI model (or do anything else, really) is bad… well, that’s exactly what you’re going to get.

If you want to learn—in the most fun and entertaining way—how NOT to collect and curate a dataset, I highly recommend this episode by the hilarious John Oliver, on the “gang databases” maintained by police departments in many U.S. states.

I bet you can spare twenty minutes while you munch on your August breakfast.

It’s super educational. It would all be very funny, too—if the crude biases and selection errors mocked in the episode didn’t have terrible consequences for the people listed (mostly—surprise, surprise—Black and Hispanic individuals).

4.- Deldits case: The accuracy of data is judged according to the purpose of processing

Context is king in personal data protection. That is, privacy is deeply contextual—I say it all the time.

VP, an Iranian citizen, was granted refugee status in Hungary in 2014 by claiming her transgender identity.

Why? Because in Iran they simply execute people who feel (and especially: express) a gender different from the one assigned at birth.

Despite basing her asylum claim on being a trans person—with medical certificates stating that although she was born female, her gender identity was male—VP was registered as female in Hungary’s asylum records.

In 2022, VP exercised her right to rectification, essentially saying: “Dear Hungarians, it seems you've made a silly mistake: you misrecorded my gender—the very reason you granted me asylum. Please fix it.”

The competent authority denied the request, requiring proof of sex reassignment surgery.

To make matters worse, since 2020, not only refugees —but even Hungarian nationals— cannot legally rectify already-registered gender identity.

The case reached the CJEU, which, applying rights recognized under the European Charter, ruled:

The accuracy of data must be assessed in light of the purposes of processing.

In this context, "updating processed data is an essential aspect of the protection of the individual concerned in relation to the processing of such data."

The national authority must rectify personal data regarding a person's sex when it is inaccurate (Articles 5.1.d and 16 of the GDPR, and 8.2 of the Charter).

The administrative requirement for proof of surgery is insufficient, unnecessary, and disproportionate: Limiting fundamental rights (as is the case here) requires a legal provision that also respects the essence of the right to personal integrity and the right to private and family life (Articles 3 and 7 of the Charter).

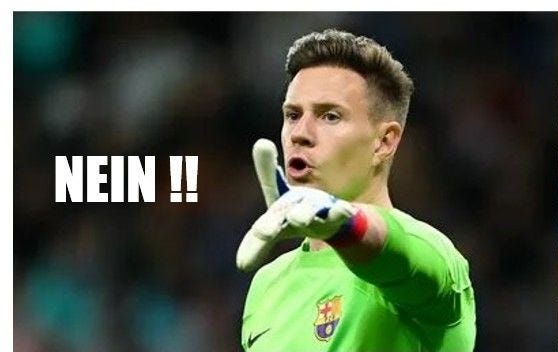

5.- “Only yes means yes”, by Ter Stegen

Football players are also human beings and have the right to data protection.

Can a professional player’s contract—which basically involves... playing football—be fulfilled without it being absolutely necessary for every random person on the internet to know the latest updates on a goalkeeper’s health?

Yes, darling.

Therefore, the player's consent is required to share their health data with any organization, to make it public in the press, or to send it to platforms that calculate their market value like they were tuna or crypto.

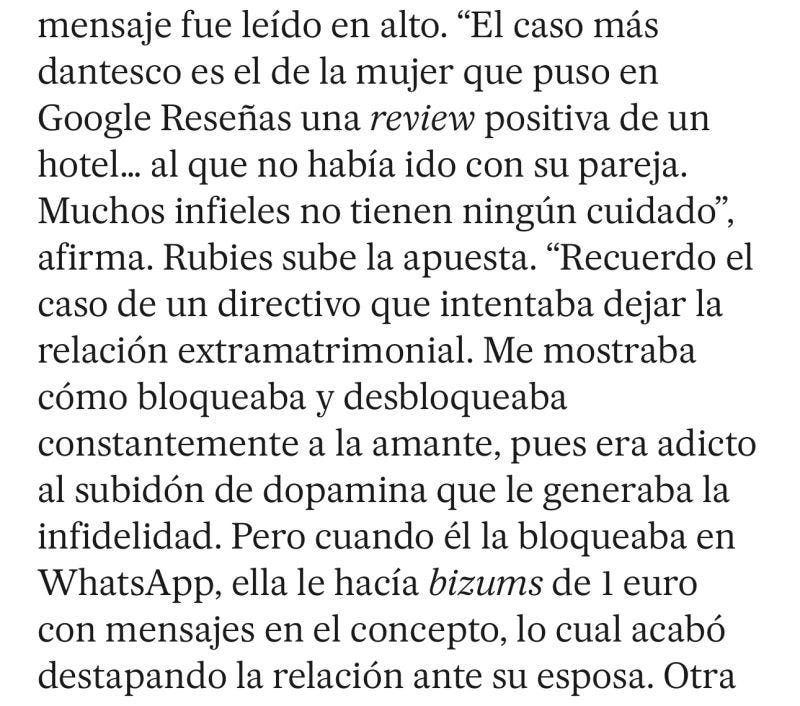

6.- Reality ALWAYS surpasses fiction

When it comes to "domestic data breaches," the Netflix series Alpha Males is the gold standard.

The kids' tablet set up with the same access privileges as the mother’s account, the clueless husband saving things in work folders without realizing they're shared, Siri saying “looks like you're riding a horse” based on the fitness band sensors (and no, it’s not a horse)...

The producers and writers of the show say all these bloopers are based on real events.

And when you read the article in the screenshot above, it’s clear that real life ALWAYS (ALWAYS) beats fiction...

7.- Bonus track (this one's from July): In the EU, Coldplay would've been slapped for the KissCam incident

We all saw the now iconic moment at the Coldplay concert.

The "Kiss Cam" showed in glorious 4K an older couple who—well—were married, just not to each other. “Don’t panic.”

Would this be legal in Europe under the GDPR?

No, darling.

To process and broadcast your image, they need your consent. That’s why you sign a contract with your kids’ daycare and then they separately ask for your consent to post photos of the crafts they made on their website.

“Trouble”: The couple caught on camera could file a complaint with the AEPD and sue for civil damages:

(i) Coldplay and

(ii) the concert promoter (the company operating the KissCam and the giant screens), at the very least.

It’s not enough to “accept” some terms and conditions when you buy a ticket: in Europe, we are protected.

It’s possible that the concert promoter covers themselves in their privacy policy, but what Coldplay does with their damn "Kiss Cam" requires prior consent from the “lucky” ones on screen.It doesn’t matter if the individuals caught were “morally in the wrong”: it’s irrelevant whether they were adulterers or turned their spouses into deer. That’s not how the fundamental right to data protection works, thankfully. “Viva la vida”

Chris Martin plays “show director” and doesn’t even handle the situation gracefully. Worse yet, seconds later, he accepts fault: “I hope we didn’t screw anything up here.”

Sigh.

Coldplay and the promoter (at the very least, I repeat) are jointly responsible for the massive and non-consensual dissemination of an image that is personal data—with irreparable consequences for the individuals involved.

Those two are now just more stars in “A sky full of stars”—but not in the way they imagined.

Special mention goes to the usual OSINT “hacktivists,” always ready to pile on, who worked at “the speed of sound” to identify the couple: their names, companies, job titles, and family details were all revealed in no time.

And if they can be identified (they always can—they’re after attention), they too could face fines and—this is less clear—civil liability.

Jorge García Herrero

Abogado y Delegado de protección de datos

If you think this newsletter might be interesting or even useful to someone, forward it.

If you’re missing a doc, a comment, or some juicy nonsense that clearly should’ve been in this week’s Zero Party Data, write to us or leave a comment.