AI vs GDPR: Three alternative paths to compliance

Because sometimes, legitimate interest is not enough...

[Golden Girls´ Sophia Petrillo speaking]: “Remember: Europe, December 18, 2024”

DPOs from all over Europe (and some from abroad) have one eye on the Christmas holidays and the other on the EDPB website, which is due to publish its Opinion 28/2024 on the processing of personal data in the context of Artificial Intelligence models.

Many hopes are pinned on this text, although the outlook is far from promising.

And it is confirmed: once read, the document does not untie any of the Gordian knots that “cripple innovation” in the European Union.

There is nothing useful in it to facilitate the legitimization of things such as (i) the gathering of those enormous datasets used to train all those hegemonic multimodal models, nor (ii) the very training of those models.

Or is there? Let’s see:

1.- The contractual basis

Let’s start with the most bitter pill to swallow: having to eat one’s own words.

Three things became clear following the heavy blow dealt by the Irish DPC to Meta in 2024 (okay, it was the DPC’s hand that enjoyed the glorious lateral contact with Meta’s since-battered cheek, but the EDPB was jointly responsible for the move—albeit without direct contact with personal data).

Contract and consent should not be confused.

A contract can only legitimize the portion of processing that is strictly necessary for, well… fulfilling the contract.

The contract must bind both the data subject and the controller.

That was how I had interpreted it for a long time.

Damn, in fact, that is explicitly stated in documents such as the DPC’s guidelines on legal bases for processing (p. 11) or in many rulings by the AEPD. A recent one: this one from a few weeks ago.

This interpretation is protective in nature, and the control authorities’ intention is obvious.

After all, Meta, for example, invoked compliance with contracts it signed with companies to which it sells personalized advertising… to legitimize its processing of user data.

And yet, good intentions do not always escape the long shadow of the #DeluluDickhead. And I’m speaking for myself here.

Because it’s easy to think of situations where processing is indeed legitimized, yet there is no direct contractual relationship—only an indirect one—between the controller and the data subject.

For example, a film actor or singer signs a contract with a production company, granting all rights related to a recording (of their image and voice—personal data indeed) and authorizing its distribution and use by the production company, distributors, and, through them, as many third parties as possible.

Because the more third parties publish, disseminate, project, or otherwise process that personal data, the more money every link in the chain will earn.

And obviously, neither the actor nor the singer will sign contracts directly with every nightclub that plays their song or every cinema that screens their movie.

There is no direct contract, only a master contract that allows for a transfer of rights—universal or with specific limitations.

Seen this way, it seems that if we have contracts whose purpose is a universal assignment of rights (allowing use for any purpose and/or by any third party of certain personal data—such as an image or voice), then this contractual basis could be valid for many things, including training AI models.

Even if the data subject is not a party to the contract.

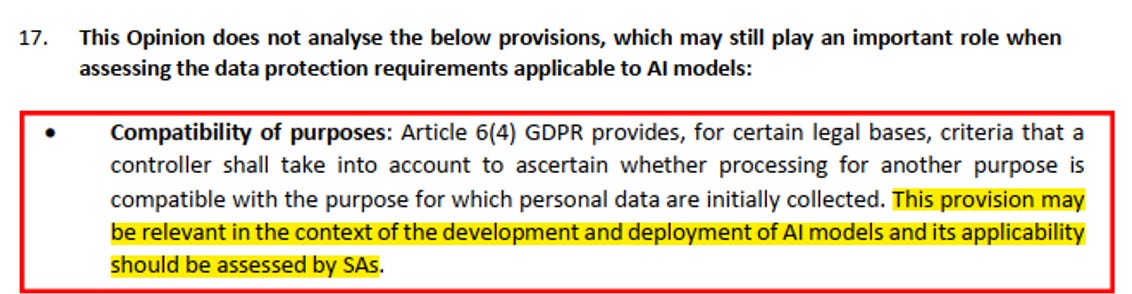

2.- Further processing for compatible purposes

We are used to the strict interpretation of the purpose limitation principle—one of the old rockstars enshrined in Article 5 of the GDPR.

However, what Article 5 actually says is that:

(i) Data must be collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes, and

(ii) Such data may not be further processed for purposes incompatible with those original purposes.

It does not say they cannot be used for anything else.

Nor that they cannot be used by anyone else.

Only that they cannot be used for anything incompatible.

Which is very different.

I’ve been saying all of 2024 in my training sessions that the compatible-purpose pathway is as promising as it is underexplored—at least when it comes to artificial intelligence.

Since last December, the EDPB has also said so in the much-discussed Opinion 28/2024.

I’ll leave that there.

3.- Lessons from “Social Media Listening” (a form of “data scraping”)

Social media platforms (including both social networks and digital versions of traditional media) have democratized freedom of expression and information.

They have given a voice to anonymous citizens, allowing them to gain traction and popularity to become “citizen journalists” or “visible faces of a shared opinion”—entirely on their own, without relying on traditional media.

This phenomenon has led to a significant increase in public exposure (with all that entails), especially for those who attain the status of Influencer or Key Opinion Leader in specialized terminology.

Social Media Listening emerges as a hybrid between traditional public opinion surveys or representative metrics from the 20th century and today’s ability to capture the opinions of an entire community present on a given social network—weighted according to the varying influence of its members.

How is the massive data processing involved in Social Media Listening legally justified?

In short: an anonymous citizen who becomes an influencer proportionally loses their privacy protection under data protection laws.

As is my habit, I find extreme examples to be the most illustrative. I’ll save a more balanced and visual example for next week, but in the meantime—read this article on the Netflix reality about the famous singer Aitana (Spanish, sorry).

Second part here:

Jorge García Herrero

Lawyer & Data Protection Officer

I love this post mostly for the dick-grabbing meme for personal data and I need to use it always and forever.