Biometric Control vs AEPD: Yes, You Can (Part 1)

This is not so clear in Spain lately

1 Be yourself today: the problem

In recent years, Spanish companies have widely adopted biometric entry controls, and subsequently, workday monitoring systems.

This type of processing was not regulated under the data protection laws prior to the General Data Protection Regulation (hereinafter, “GDPR”), which has been applicable since May 2018.

The GDPR included certain biometric data processing within the general prohibition outlined in Article 9.

The AEPD, through successive resolutions, reports, and guidelines, began to establish criteria and admissibility requirements, which were initially flexible.

However, the publication of a new specific Guide in November 2023 surprised everyone by tightening these criteria and requirements, creating an unprecedented (and controversial) situation of legal uncertainty.

This text aims to achieve three objectives:

· To highlight an issue in the 2023 Guide that needs to be addressed.

· To focus the debate on the necessity of the processing.

· To suggest a pragmatic solution based on a criterion from the EDPB that has always been present.

Furthermore, taking advantage of the public consultation period opened by the AEPD, this text will be submitted as a proposal for consideration in connection with its five-year Strategic Plan.

You’re reading ZERO PARTY DATA. The newsletter about the crazy crazy world news from a data protection perspective by Jorge García Herrero and Darío López Rincón.

In the spare time this newsletter leaves us, we like to solve complicated issues in personal data protection. If you’ve got one of those, give us a little wave. Or contact us by email at jgh(at)jorgegarciaherrero.com

2 What Constitutes “Biometric Data” and “Biometric Processing”? Ah, the confussion

Article 9.1 of the GDPR states:

“Processing of (…) biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person shall be prohibited (…)”

Since the publication of the GDPR, there have been a range of opposing interpretations regarding what is or is not considered biometric data and, more importantly, what constitutes prohibited biometric data processing.

2.1 “You Too, Brutus”

Not even the EDPB is without sin. The very Sanhedrin of data protection got itself tangled up in the 2021 guidelines on voice assistants.

In one part, it says:

“The EDPB recalls that voice data is inherently biometric personal data.”

… and further on, it literally acknowledges the opposite:

“GDPR considers that the mere nature of data is not always sufficient to determine if it qualifies as special categories of data since ‘the processing of photographs […] are covered by the definition of biometric data only when processed through a specific technical means allowing the unique identification or authentication of a natural person.’ (Recital 51) The same reasoning applies to voice.” (Emphasis added)

2.2 So… Can Someone Please Explain What Exactly Is Prohibited?

The processing of health data or data on sexual orientation is prohibited, regardless of the purpose of the processing.

In those cases, to put it simply, one could speak of “prohibited data.”

However, strictly speaking, there is no such thing as “prohibited biometric data”: what the GDPR prohibits is the processing of biometric data with the purpose of uniquely identifying the data subject.

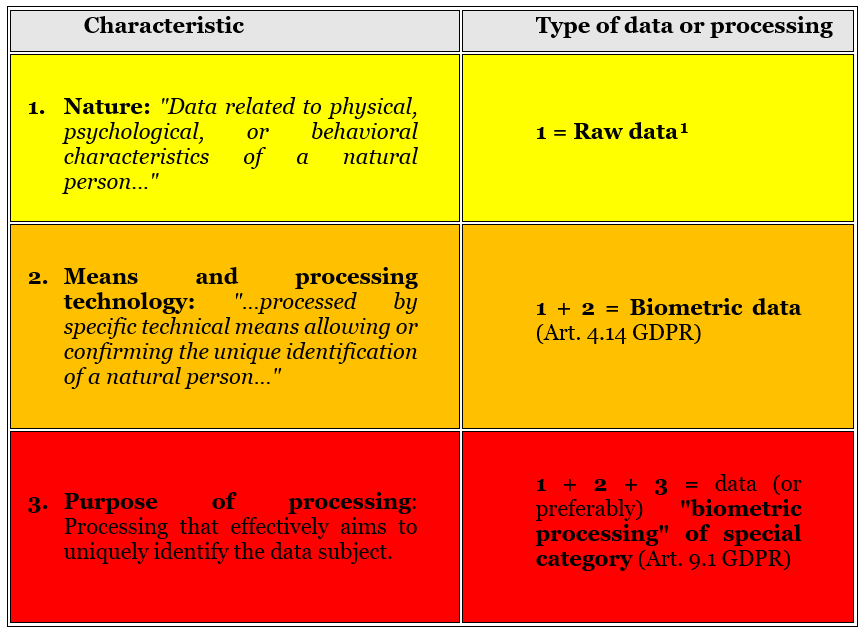

In short, the processing of biometric data is only prohibited when all three of the following characteristics are present.

In line with the above, if the processing of biometric data is intended to detect physical characteristics to profile individuals, but without identifying them (their sex or age, for example), then there is processing of biometric data, but it is not prohibited under Article 9 (unless the processing infers other data included in Article 9.1 of the GDPR).

That said, in the employment context, it is common for these controls to be aimed at identifying each employee, either to grant them access to the premises or to register the start and end of their working hours.

3 Has This Always Been the Case?

Of course not. In fact, it has changed quite a lot.

3.1 The Good Ol' Days

Since 2019, a popular interpretation across Europe held that the processing of biometric data was only prohibited if it identified the data subject "one against several possible candidates" (biometric identification), but not if it simply authenticated their declared identity against their own personal data "one to one" (biometric verification or authentication).

This interpretation was based on a 2012 Opinion from the EDPB, that is, prior to the GDPR.

However, the EDPB’s Guidelines 5/2022 on facial recognition for law enforcement purposes marked a turning point from that previous stance:

“While both functions – authentication and identification – are distinct, they both relate to the processing of biometric data related to an identified or identifiable natural person and therefore constitute a processing of personal data, and more specifically a processing of special categories of personal data.”

3.2 The 2021 Guide on Data Protection in Employment Relationships

The Guide on data protection in employment relationships introduced several changes that facilitated the adoption of biometric processing:

The aforementioned distinction between authentication and identification, excluding the former from the scope of the prohibition under Article 9 of the GDPR, in line with the dominant interpretation at that time within the European Union.

The acceptance of the legitimacy of worker controls – in general – based on Article 20.3 of the Workers’ Statute (employer’s supervisory power) and their incorporation into the set of obligations constituting the employment contract (i.e., in principle, the contractual basis under Article 6.1.c) of the GDPR was accepted). This route was notably simpler and more convenient for companies than that of legitimate interest.

The AEPD acknowledged the legal obligation to monitor working hours as falling under Article 9.2.b) of the GDPR, thereby enabling the use of biometric systems for worktime tracking.

Lastly, the AEPD accepted the inclusion of such control systems in collective bargaining agreements as an alternative basis under the “legal obligation” framework.

3.3 The 2023 Guide on Presence Control Using Biometric Systems

In short: the 2023 Guide did not merely shift its position on all the permissive developments of 2021; it also questioned the viability of consent as a last resort. And it did so in the abstract—that is, in all cases.

In its 2023 guide, the AEPD maintains that:

The processing of biometric data falls under the prohibition of Article 9.1 whether its purpose is "authentication" or "identification."

This change came as little surprise to most, as the AEPD simply adopted the revised stance published by the EDPB in the final version of its Guidelines 5/2022 on facial recognition for law enforcement purposes, mentioned earlier.

The “legal obligation” can serve as a general basis under Article 6, but not as an exception under Article 9.2 of the GDPR, because while the Workers’ Statute mandates monitoring, it does not specifically require that such monitoring be biometric.

This change also did not surprise many. It appears to stem from rulings such as the CJEU’s judgment in Case C-205/21 (January 26, 2023). This ruling analyzes and applies not the GDPR, but Directive 2016/680 (the Law Enforcement Directive) under Bulgarian law:

“(...) national legislation that provides for the systematic collection of biometric and genetic data of any person investigated for a public criminal offense is, in principle, contrary to the requirement set out in Article 10 of Directive 2016/680, which states that the processing of the special categories of data referred to in that Article shall be allowed only when it is strictly necessary.”

The employment contract is not a valid legal basis for processing, since biometric access control fails the proportionality principle (based on the notion that historically, there have been equally effective methods for the same purpose that are less intrusive in terms of privacy, making biometrics not strictly necessary).

The most controversial point: the consent route is effectively closed off by the AEPD’s three-step reasoning:

(i) Explicit consent added to the employment contract to legitimize biometric processing must be freely given;

(ii) Consent from an employee is especially difficult to prove as freely given, and therefore requires, as a necessary condition, the offering of a functional or operational alternative;

(iii) According to the AEPD, if a viable non-biometric alternative exists, it becomes difficult to argue for the “proportionality,” or indeed the strict necessity, of biometric control.

Finally, the collective agreement route remains operational, but is now “reinforced” with new requirements: the provision for biometric control in the agreement must explicitly define the scenarios and safeguards applicable to the processing.

Mini-Conclusion

This whole explanation is meant to provide context for the situation that has developed: privacy specialists were expecting several of these changes in criteria in the fall of 2023, as we were aware of the background developments.

However, the controversial “three-step” argument concerning consent caught everyone by surprise.

And it created an undeserved state of uncertainty for those organizations that had implemented biometric controls in response to objective needs.

Suddenly, they found themselves in a state of illegality, with no clear path to legitimize their processing.

Because the key to clarifying this whole mess is this: objective necessity.

The second part of this post, in this link

Jorge García Herrero

Delegado de Protección de Datos