Deepfakes vs GDPR: Prohibited biometric processing?

Is generating a deepfake biometric processing that allows the unique identification of the data subjetc? I say it is

Today I’m going out on a limb and claiming that non-consensual deepfakes can be sanctioned, not just for lack of a legal basis (consent) but also as a prohibited form of biometric processing.

Have these Romans gone mad? Well, I’m saying this with the backing of decisions from enforcement authorities.

But let’s start at the beginning:

Deepfakes are image, video, or audio outputs generated by artificial intelligence that plausibly recreate real people.

At a time when deepfakes are receiving maximum media attention (anybody said Grok?) and prompting announcements of a tightening of the applicable legal regime, we examine the issue in light of the most recent case law and decisions by authorities.

Just in Spain, during February we saw the launch of a new draft law regulating the Right to honor, personal and family privacy, and one’s own image explicitly including deepfake as an unlawful intrusion.

On Thursday, not to go any further, the proposal by the European Parliament to include the generation of non-consensual sexual deepfakes as a new prohibited purpose in the Artificial Intelligence Act was announced. This measure will fix nothing, for reasons we explain here.

Do all AI-generated images violate the GDPR?

Of course not.

We have good reasons to argue that image, video, or audio outputs that include “random” natural persons generated by generative AI models do not constitute processing of personal data by default, unless:

(i) the model has been specifically trained to include identified people in the output, or

(ii) they start from content as a template and are capable of generating an output that can be plausibly confused with those people.

In the second case, we would already be entering “deepfake territory”.

Deepfake as prohibited biometric processing

My thesis is that a good deepfake, a recent one, the kind that is almost impossible to distinguish from reality, is the result of biometric processing of the prohibited kind under Article 9 of the GDPR.

Yes, you read that right. No, I haven’t gone crazy.

Qualifications:

· Of course, the deepfake must include still image, video and/or voice of natural persons.

· I am not referring to the fact that they depict the cloned person in circumstances or a disposition related to a particular sexual orientation, political ideology, health data, etc… I am talking here about “biometrics.”

· I am not arguing that personal data protection is the best route, nor the only one to tackle the problem—for example of non-consensual sexual deepfakes. What I am saying is that, IMHO, today it is one route, with an unexplored sanctioning potential.

As I imagine you’re making funny faces, let’s get to it.

You’re reading ZERO PARTY DATA. The newsletter on current affairs, technopolies, and law by Jorge García Herrero and Darío López Rincón.

In the spare moments this newsletter leaves us, we specialize in solving complicated stuff in personal data protection. If you have one of those, give us a little wave. Or contact us by email at jgh(at)jorgegarciaherrero.com

Thanks for reading Zero Party Data! Sign up!

1 Is a deepfake personal data?

Without any doubt: When a deepfake includes a person’s face, body, movements or voice, its generation entails the processing of their personal data to the extent that the data subject is identified or identifiable.

And that is so even if they are not identified by direct identifiers (name, surname, public office, etc.).

According to CJEU case law it is sufficient that the processing allows the data subject to be identified or identifiable or else individualizable within a specific group of people.

2 Does the generation of a deepfake entail processing of biometric data?

Warning: In this muggle-friendly format I’ll spare you the bulk of the unbearable technological and legal mumbo jumbo I’ve had to swallow, and therefore, I am giving up on being completely rigorous in favor of being understandable.

Classifying the generation of deepfakes as biometric processing prohibited by the GDPR depends on two elements:

a. The technological architecture used by the generative AI system

b. How the concept of “unique identification” in Article 9 GDPR is interpreted.

2.1 From the technical point of view:

Not so much the systems from a few years ago, but certainly modern video deepfake generation systems (Diffusion Transformers, models like Sora or Veo) systematically extract biometric features during their operation.

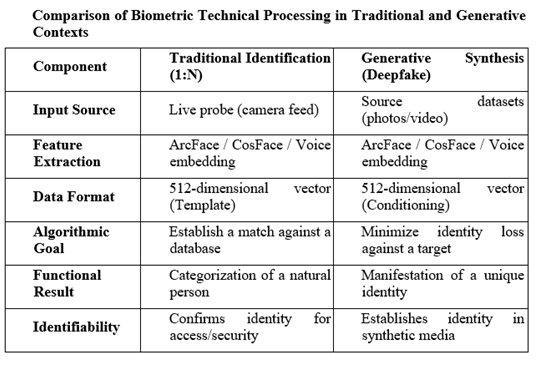

Whereas in traditional architectures it could be maintained that latent representations did not constitute “biometric templates” in the strict sense, modern systems use identity embeddings from facial recognition models that are functionally equivalent. Both facial recognition (ArcFace, CosFace) systems and deepfake generation systems (and deepfake detection ones) use an identical technical infrastructure: 512-dimensional embedding vectors that encode unique facial features.

Of course, in video, although the mathematical operations are identical, the functional purpose differs:

· Identification is analysis (image → identity decision), whereas

· The generation process is the inverse: synthesis (identity embedding → image).

This, however, does not call into question that both processes enable the unique identification of the person who is the subject of a deepfake.

In the realm of orthodox biometric identification, vectors are used as “templates” against which a person’s metrics are compared to establish their identity.

In synthesis (generation), the model is technically carrying out a continuous process of “identification” both during the training phase and during inference.

The generator is essentially being ordered to produce a recreation that would be uniquely identified as the target person by any recognition system.

The integration of the purpose of “matching” into the “generative” purpose is eloquent regarding the relevance in both processes of the data that enable unique identification, satisfying the criteria of Article 4(14) of the GDPR.

That is, the processing of biometric data is undeniable.

If we are talking about audio deepfakes, the matter is even clearer: it entails biometric processing capable of identifying the data subject and, in fact, the processing of customers’ voices for the purpose of biometric identification is commonplace in the banking sector to prevent fraud.

2.2 From the legal point of view, “unique identification” is interpreted—so far—differently

The concept of “unique identification” of the data subject has traditionally been understood as authentication of identity (1:1) or as identification (1:n).

The issue—which I argue—is whether it would fit within the concept of “unique identification” in Article 9 that the data subject themselves is identified (in the deepfake), not (i) by the controller—as in the case of authentication/identification—but rather (ii) by third parties who see, hear, or have access to the synthetic deepfake:

· — The deepfake output “is identified” with the data subject.

· — Third parties “identify” the data subject uniquely.

Recital 51 of the GDPR establishes that the processing of photographs should not systematically be considered processing of special categories, “as they are only covered by the definition of biometric data where they are processed through specific technical means that allow the unique identification or authentication of a natural person.”

The orthodox or teleological interpretation—dominant until now—focuses on the purpose of the processing: if the purpose is not to identify in a system (1:n), or to authenticate (1:1), biometric processing under Article 9(1) is not deemed present.

If this criterion is maintained, deepfakes—whose purpose is to create synthetic content identifiable with a person, but not to verify identities—would not trigger the prohibition in Article 9.

And all this, without getting into:

.- The prior extraction of biometric data from the data subject’s original image or video—which occurs only in some cases, in video generation—but always in the case of voice—for the generation of the deepfake.

.- As I said before, the fact that the content and circumstances of the deepfake allude to the data subject’s special category data (it doesn’t matter whether they are true or false: according to the CJEU they are still personal data).

2.3 What has the AEPD said?

Data protection authorities have hardly spoken on this issue.

In fact, the first case was the AEPD’s decision on the Almendralejo case.

In it, a penalty was imposed for processing personal data without a legal basis (infringement of Article 6 GDPR) without ruling on the biometric issue put forward here.

However, the precedent seems unrepresentative because, despite the seriousness of the facts and the social alarm and media attention of the incident, the fine was moderate in view of the prior criminal penalty and the financial situation of the parents who had to shoulder the civil consequences of the conduct of the reported minor.

2.4 CJEU case law:

According to CJEU case law:

· The enhanced protection of sensitive data requires an extensive interpretation of them (and this in guarantee of the protection of a fundamental right—the right to personal data protection—but one must bear in mind that in a sexual deepfake, others will likely concur as well).

An eloquent manifestation of this extensive interpretation was the inclusion of authentication (1:1) processing as prohibited biometric processing just like identification, after no small number of doctrinal back-and-forths and positions by national authorities.

· Even if the data published about your life or sexual orientation are false, they are still “sensitive data” (special category).

· It is enough that sensitive information “can be inferred” from some data to consider them special category data, regardless of whether that is the controller’s purpose or even whether the inference is 100% accurate.

According to the above, one could speak of unique identification of the data subject in the “deepfake output”:

· …if the technology involved is the same, and

· …if the same technology not only allows the Controller to identify the data subject (1:n) but also allows the data subject to be identified by “everybody and their dog” with access to the deepfake.

That is, if the result of the processing allows the unique identification of the data subject—understood as any third-party observer unequivocally identifying the impersonated person—the processing could be understood as prohibited biometric processing.

2.5 The Italian Garante’s “warning.”

The Italian Garante has been the first European authority to admit (indeed: to warn) expressly in December 2025 a broad interpretation of “prohibited biometric processing”, publishing a “warning” to the effect that deepfakes could constitute processing of biometric data when the result allows the identification of the impersonated person by third parties, regardless of the system not operating as a traditional identity verifier.

“CONSIDERING that voice and images can, certainly, be included among the so-called identifiers, that is, that category of information that has a direct relationship with the identified person and, therefore, such vocal or visual identifier may be classified in the category of biometric data if certain specific criteria are met*. These consist in the nature of the data, which must refer to a physical, physiological, or behavioral characteristic of a person, and in the means and purposes of the processing carried out which* must consist of technical processing for the purpose of unique identification; in this case, it is, therefore, necessary not only to verify the existence of a legal basis in accordance with Art. 6 of the GDPR, but also of one of the conditions indicated in Art. 9(2) of the GDPR*. A necessary condition also in the case that the voice may be included within the scope of special categories of data.”*

(…)

“FOR ALL THE ABOVE REASONS, THE GARANTE:

a) pursuant to Art. 58(2)(a) of the Regulation, warns all natural or legal persons who use, as controllers or processors, content generation services based on artificial intelligence from real voices or images of third parties, that such processing of personal data, if carried out in the absence of an appropriate condition of lawfulness and without correct and transparent information being previously provided to data subjects, may, plausibly, infringe the provisions of the Regulation, in particular Arts. 5(1)(a), 6 and 9 of the Regulation, with all the consequences, including sanctions, provided for by the personal data protection legislation;

b) pursuant to Art. 154-bis(3) of the Code, orders publication in the Official Gazette of the Italian Republic.”

If you read the entire doc, you will see that it is addressed not only to users but also to platforms that make deepfake generation means available to them.

3 Background in comparative law

3.1 BIPA in Illinois (USA)

Under the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act (“BIPA”) the concept of “biometric identifier” explicitly includes “scan of hand or face geometry,” a term that precisely describes the technical process of extracting facial embeddings.

The critical distinction is that while photographs are excluded from the definition of biometric identifiers, face geometry scans derived from photographs are not.

Meta settled a “sanctioning agreement” for $650 million for extracting face geometry from photos uploaded to Facebook by its users (which constitutes collection of biometric identifiers under BIPA) without their consent.

The Illinois Attorney General published in February 2025 an open letter on Gen-AI models (specifically Grok), expressing concern that “the AI model may be scraping biometric data, in violation of BIPA, to create its deepfake images.”

Additionally, face-swap services like SwapFaces AI already market themselves as “BIPA Compliant,” implicitly assuming the applicability of the law.

3.2 The Chinese regulation is even clearer

The Provisions on the Administration of Deep Synthesis Services (effective since January 2023) explicitly regulate the generation and editing of biometric features in deepfakes.

Article 14 establishes that deep synthesis service providers offering functions for editing facial or voice biometric information “must require users to notify the person whose personal information is being edited and obtain their separate consent.”

Article 23(4) defines deep synthesis to include “technologies for generating or editing biometric characteristics in image and video content, such as face generation, face swapping, personal attribute editing, facial manipulation, or gesture manipulation.”

Therefore, and unlike the GDPR, China’s PIPL does not condition the classification of biometric data on the purpose of unique identification—the classification is based on potential harm, not on the purpose of the processing.

3.3 Brazil

Brazil (a country newly deemed adequate to the GDPR) published a few days ago in relation to the Grok case, the ANPD Technical Note 1/2026, which establishes that

“synthetic content generated by generative AI systems, when it refers to identified or identifiable natural persons, must be considered personal data”

and that:

“when such activity involves the use of biometric data, the resulting synthetic content will assume the status of sensitive personal data.”

4 What sanctioning effect would my interpretation have?

Depending on the circumstances of the specific deepfake, two, three, four… infringements of the prohibition on processing special category data could be found.

The GDPR does not allow multiplying the number of infringements found in these cases, but it does allow sanctioning the most serious infringement at its highest level. And we all know how high GDPR fines can go.

Here, yes, the stakes are sky-high, and public and media attention is at a maximum.

It is only a matter of time before someone reports correctly and some authority delivers the surprise.

Jorge García Herrero

Lawyer and DPO