High-level analysis of Atlas, OpenAI's new browser

“Be very careful out there.”

What follows is a high-level analysis of OpenAI’s “Atlas” architecture and the most striking risks in light of the GDPR and the AI Act (RIA).

It addresses corporate use of Atlas and does not delve into the obligation to carry out a DPIA or its content (we want to maintain a certain level of seriousness), nor into questions of international data transfers or contractual measures for vendor selection or ensuring accountability on their part (we’re talking about OpenAI).

You are reading ZERO PARTY DATA. The newsletter on tech news from the perspective of data protection law and AI by Jorge García Herrero and Darío López Rincón.

In the spare time this newsletter leaves us, we like to solve complicated issues in personal data protection and artificial intelligence. If you have any of those, wave at us. Or contact us by email at jgh(at)jorgegarciaherrero.com

Description of the Tool

Atlas is a browser with integrated ChatGPT functionalities, currently available only for iOS and only for paid tiers (Plus, Pro, Business, Enterprise/Edu).

The flow includes a central LLM (ChatGPT), persistent memory (“browser memories”), agentic layer (actions/tools), interaction with APIs and external data sources.

The use of subprocessors/external cloud providers (BigQuery, GCP, AWS) is not declared, except for specific integration via agents; mapping them in a DPA is recommended.

Available documentation does not indicate an automatic TTL policy for memories, logs, or persistent context: deletion/archiving is manual.

Executive summary or quick takeaways

Yes: this comes first because we know almost no one will read 2,500 words of text.

Atlas is geared towards personal productivity, with agent functionalities and persistent contextual memory.

Multiple categories of personal data are collected and processed: history, chats, “browser memories,” imported passwords and bookmarks.

The legal basis inferred from available documentation is (”performance of contract” – terms and conditions). This basis is highly debatable from a rigorous standpoint. That said, explicit consent is requested to enable training purposes.

The user controls visibility, persistence, and training of data. YES BUT: (i) their consent is captured using numerous dark patterns, and (ii) there are risks of all kinds in persistent memory contexts and agent use.

The Tool’s architecture involves processing by OpenAI (Provider) and control by the user or their organization (Deployer).

Documented controls exist for minimization, TTL, and access, but retention/logging policy lacks timelines; control falls to the user, which always undermines any assessment of the provider’s accountability.

The agentic flow and integration of external sources (email, docs) amplify risks of propagation, exfiltration, or unintended inference of personal data, mainly but not only due to the risk of prompt injections.

It is not identified as a high-risk system under Annex III of the AI Act, but its use in any organizational environment requires a DPIA due to innovative technology, data access and combination, large scale, and potential inference of special categories, off the cuff.

Mini-analysis GDPR — Legal basis, transparency, minimization

Legal basis:

· Main functionality: Inferred from available documentation: performance of contract (Art. 6.1.b), but strictly speaking this basis would only cover processing strictly necessary to fulfill the promised functionality of the Tool (chat, browsing, responses).

· Training of OpenAI AI models: Requires explicit consent (Art. 6.1.a GDPR); the user must enable the “include web browsing” option for their content to be used for this purpose.

Transparency:

The user controls the visibility and persistence of memories, but it must be clarified how previous ChatGPT configuration affects Atlas (recommendation: specific onboarding and instructions should be implemented—Atlas can be really heavy-handed in obtaining user consent).

Mini-analysis AI Act

Provider: OpenAI (ChatGPT Atlas) is the provider and must determine system robustness, security, and conditions of use.

Deployer: The organization offering Atlas to its employees (or subjecting third parties to, e.g., the effects of Atlas in agentic mode) acts as the deployer, assuming control over usage, configuration, orchestration, logging, and human oversight.

Other roles: Agents/external sources may act as subprocessors or independent third parties (email, docs, web).

High risk (Annex III): Classification as high risk does not apply per se (productivity/personal orientation), but agentic functionality (autonomous actions) implies significant security and privacy risks and requires constant monitoring and active user warnings.

Data flow and key issues

Atlas integrates several distinct flows that, together, form a complex architecture prone to cumulative privacy risks.

Direct user–ChatGPT interaction

The user interacts with the Atlas browser by opening a new tab, entering a URL, or typing a natural language query. This request is sent to the LLM engine (ChatGPT), which processes it, searches, and reasons contextually to return an enriched response, potentially including links, images, videos, or relevant excerpts. The cycle is immediate and aims to provide support or assistance during browsing.

Note: The user’s input may contain personal data, which may also fall into special categories.

Big caution: Moreover, due to Atlas’ design, the response may be personalized based on previous persistent contexts (browser memories), expanding the potential exposure window of PII.

This is a major issue hidden in plain sight: the user using Atlas may not necessarily browse traditional websites, but rather an amalgam of synthetic content generated by ChatGPT through an interface that looks like a browser.

Persistent memory of browsing data

Atlas incorporates a persistent contextual memory functionality called “browser memories,” through which the system extracts, stores, and reuses key details from web browsing.

This process occurs when “visibility” is enabled and may include anything from text fragments to interaction metadata (times, usage patterns, visited pages).

Implications: Unlike traditional history, these memories are actively used to enrich future ChatGPT responses, offering personalized suggestions and intelligent reminders (e.g., about articles viewed weeks ago).

Control and risks: There is no automatic TTL; management is manual and up to the user: memories can be archived, viewed, and deleted, but their default persistence increases the risk of inference on habits, interests, and special data categories (e.g., health, finances, ideology), as the reference document itself warns. Control of these memories is crucial, as their use may lead to detailed behavior and preference profiling.

Agentic functionality and access to external tools

In agent mode, ChatGPT can execute autonomous actions beyond simple text generation.

This includes interacting with external sources (email, document repositories, spreadsheets), conducting automated research, filling out forms, and even making purchases or reservations.

The user retains the ability to pause, interrupt, or supervise the agent at any time.

Issue: This layer increases the risk of accidental or massive exfiltration of personal data by

(i) allowing prompt injections, and

(ii) connecting ChatGPT with third-party APIs that may operate under privacy and security standards misaligned with those of OpenAI or the end user.

It is essential to highlight the risk of inadvertent exfiltration of personal data and confidential information, excessive parameter transmission, and unmanaged context persistence in complex sessions.

Initial import

When installing Atlas, the user can import saved passwords, bookmarks, and history from other browsers. Over time, chat history and memory are stored in the user account, except when incognito mode is activated or manual deletion is performed. Pages visited by the agent are not included in the standard browser history, though the document does not detail retention of technical logs (debug) or their specific location.

Issue: Mass import of personal data (especially passwords and bookmarks) may pose a risk if the system does not apply access segmentation, strong encryption, and active monitoring. The absence of an automated log expiration or deletion mechanism reinforces the need for contractual and technical controls.

Persistence and logging

The system persistently saves both chat history and memories, without automatic TTL. Persistence may last indefinitely unless manually intervened. No logging policies are specified for debugging, nor the physical storage location (cloud/local), nor the applied encryption or access control mechanisms.

Conclusion: Be very careful with all this:

Importing passwords/bookmarks/history from other browsers.

Creating and using “browser memories” without automatic deletion directives.

Including attached web content in chats (prone to mixing private/professional contexts).

Interacting with external sources (email, docs, spreadsheets) and executing automated actions. (Time bomb).

Logging of chat history and memories, persistent unless using incognito mode. (But… does anyone still think incognito mode actually works?).

Exclusion of agentic browsing from logging, but possible persistence in other components.

More on this, with very specific third-party attack examples in the Brave blog, the Washington Post, and in this cluster post by Nazir T.

🗞️News of the Data-world 🌍

The EDPS has updated its guidance on Generative AI/GAI. We could bore you more than the above with the updates, but Joost Gerritsen explains it very well on Linkedin.

Another mess for Clearview. Now in the criminal domain from Noyb. Remember the poker of DPAs sanctioning them, the ridiculousness of these folks and their biometric database of who knows what, and the concerns from the EDPB about law enforcement using it for what we already know (indirectly, through a question submitted by the usual suspect, Sophie in’t Veld + some other MEPs).

The Italian Garante warns that on November 3rd AI training with LinkedIn data begins, for two things: so we can all object if we want, and to say it’s working with other DPAs to see if LinkedIn’s approach complies with opt-out/down and solid IL. It’s increasingly useless for avoiding junk, but it’s what we’ve got since Elmo(X).

Datatilsynet has ruled on the Scania Doctrine. It’s the first authority to do so. And in my view, they really messed it up, but that’s just my opinion.

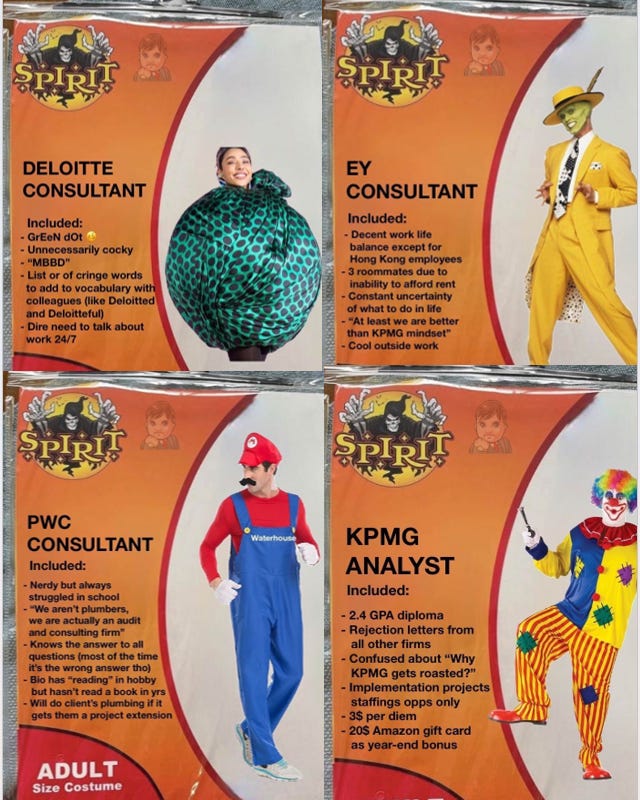

💀Death by Meme🤣

And since the day after the launch of Zero Party is Halloween, we had to mention it. A specific data-themed version could be made, but nothing will ever top what was seen on Linkedin last year. Here’s a brief selection of the four most well-known ones to avoid offending anyone, but there are more in Marc Beierschoder original post:

Until next week!

If you think someone might like—or even find this newsletter useful—feel free to forward it.