Introducing the Data Act: the Act-cess right

There´s no business like show business

I see great parallels between an Alien egg and the Data Act.

One of the few decent things to extract from the fairly awful Alien Prometheus and Covenant movies is the idea that the xenomorph, the alien, is a synthesis of the original qualities of the unfortunate host that it kills when born and of its own deadly house‑style traits.

That the creature isn’t always the same as in the iconic first film, you know.

In short: you know that this synthesis is going to be, for sure, complex to manage, but you can’t know exactly how many legs and jaws it’ll have.

That´s how I see the Data Act: an alien that will take different forms and produce different outcomes across different industries.

You’re reading ZERO PARTY DATA. The newsletter about current affairs, techno‑polities, and law by Jorge García Herrero and Darío López Rincón.

In the spare moments left to us by this newsletter, we solve complicated matters of personal data protection (GDPR) and the Artificial Intelligence Regulation (AI Regulation, also known as Data Act). If you have any such issues, give us a wave.

Or contact us by email at jgh(at)jorgegarciaherrero.com.

Have you said Data Act?

Next September 12 the Data Act, having quietly infiltrated the European legal system for more than a year, will legally blow many organizations’ — legal — ribs out that:

Either don’t know that the creature exists,

Or don’t know that they “have it within them” for almost two years — the time that it’s been “in force” — or — most likely —

haven’t yet grasped the scope of the regulation.

That Data Act… is it worse than the AI Act?

Yes.

From my humble point of view, this regulation represents a greater challenge than the AI Act, for the following reasons:

The AI Act has taken all the media noise, but it is a product‑safety regulation and narrowly applied, not like the Data Act, which applies immediately to entire sectors and has the ambition to enable the emergence of new data markets and services.

The AI Regulation is a horror of principles, exceptions and exceptions to the exceptions and so on… but you understand it when you read it.

But processing the concepts of the Data Act, the new obligations, and especially its scope in concrete cases, in interrelation with the GDPR and the rest of existing legislation, is far from easy.

It takes multiple readings, underlinings, screams of despair, notes, colors, and hair loss just to begin to see which way the wind blows.

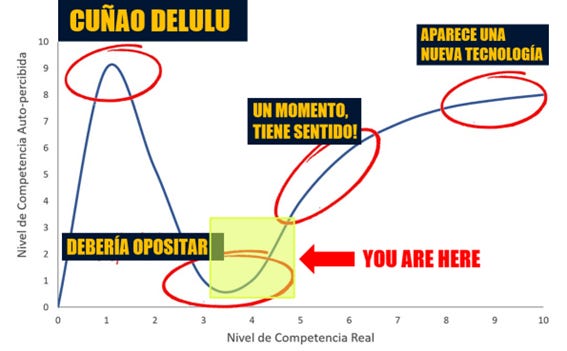

I guess with this regulation it will happen the same as with the GDPR, and later the AI Act, we will spend years wallowing in the yellow zone of the Dunning‑Kruger curve until the authorities start clarifying concepts.

“You are here”

That’s why, from the depths of the “valley of despair” , I propose—via an example (understandable, I hope, to all)—just a few of the novelties, legal derivatives, and problematic realities that will be looming over us from next September 12nd.

One piece of advice: read the post by Sergi Ariño on Citizen8’s blog before you go on.

Even if you’ve already read it, read it, read it again. It partially introduces elements such as what the regulation understands for its purposes as “data,” “non‑personal data,” “metadata”; the extraterritorial application; and the roles of data holder, user, manufacturer that I will illustrate here.

Hey! But if I tell you that it’s better… You don’t listen; you won’t read it? Suit yourself.

Now I will present a practical case like the ones I use in my training sessions. And then we will look at some—only some—implications.

The “Muskolini” case:

Scenario.

Muskolini manufactures cars. Adorable little electronic cars (Muskos) that almost, almost drive themselves.

Of course, to achieve this, they are equipped with hundreds of sensors collecting data of all kinds: on the functioning of their various components, on the user’s driving, on traffic and pedestrian circumstances around, location, speed… everything you can imagine.

Muskolini also sells the idea of “swarm intelligence.”

All the information observed and/or generated by its vehicles is processed centrally at Muskolini Inc, so it can—and does—promise that what is learned from any incident (Muskos don’t suffer accidents) suffered by one Musko, is “learned” by all others, in real time.

Muskolini distributes or sells its Muskos through a network of dealerships, dealerships that also (i) provide after‑sales services (e.g. warranty repairs, check‑ups) and (ii) buy them to rent them later.

Additionally, there are (iii) independent repair “workshops” that fix Muskos without any relationship to Muskolini, as occurs with normal vehicles.

Users

Thus these Muskos may be driven by:

Their owner (proprietor). “User” in the sense of the Data Act.

Their lessee (in the case of a rental). “User” in the sense of the Data Act.

Mini‑conclusion: to be a “User” you need to hold a “real right” over the connected gadget (or be a user of an app in connection with related services, but that we leave for another post).

Non‑User Data Subject

And Muskos may be “used” as passengers (not driven) by:

A person who is a family member, friend or acquaintance of the Musko User. This role is very interesting: they are a “Data Subject” – in the sense of the GDPR – but “not a User” in the Data Act sense. A “Non‑User-Data Subject”

To give very, very dumb (and irrelevant) examples of these Non‑User-Data Subject :

Occupants of that “connected” or “smart” home you rent through Airbnb.

Employees of a company who, to perform their work duties, use corporate connected devices (a whole universe of issues here).

Manufacturer? Data Holder? User?

Muskolini manufactures the Muskos and up to now obtains and processes the data produced by the vehicles. It is Manufacturer and “Data Holder” in the sense of the Data Act.

Now think that there are many Manufacturers who may well be but are not today Data Holders. And if they want to be — or more importantly: if they want to continue being — Data Holders in the sense of retaining access to the data, they only have until September 12 to take action.

I'll leave that there.

A dealership of Muskos does not receive real‑time data from the Muskos, but since it handles repairs, it will undoubtedly access data via the vehicle’s ports and connections, at minimum when performing diagnostics.

The dealership is:

A User — relative to the Manufacturer — if it buys the Muskos to rent them.

A Data Holder relative to its lessees (regarding the data it grabs from them and their use of the vehicle, if any).

It is a third party when it only repairs them. But, if it obtains (legitimately) access to the data generated by the Musko, it also becomes a Data Holder vis‑à‑vis the vehicle’s User.

The same occurs with independent workshops.

So what is the point of the Data Act?

Here come what I see as the main novelties we will suffer in under a month:

Do Manufacturers and Data Holders now need a contract to grab your data? Yes

Manufacturers and Data Holders (in our example, Muskolini is both) will no longer be able to access data generated by Users in their use of the Muskos without fulfilling the obligations of the Data Act.

Substantially:

(i) signing a contract with the User that governs it. And before signing anything, they must

(ii) inform their users of things like:

what data is generated,

whether it is stored on the device itself or remotely on a server and the retention period;

how to access it and/or delete it, and

their conditions of use (and onward assignment, i.e. data sales).

This is the pre‑contractual information before the contract governing those accesses (by the User) and uses — and transfers, i.e. data sales — (by the Data Holder) is signed.

And when I say Muskos, think Roombas, Alexas, connected TVs, connected sex toys, AI smart glasses, Ray‑Ban Meta, etc.

Expect tons of emails like the 2018 re‑consent frenzy with ideas like “if you continue using my gadget, you consent to this, that and everything over yonder” that you’ll have to scrutinize by clicking on this link towards a 14,000‑word text.

The fun begins now because this great idea can fly between companies, but when the user is a consumer, gulp!!

It’s going to get really interesting: tacit consent, unilateral contract changes, and imposition of abusive terms do not sit well with consumer protection law.

The right of “Act‑cess”: Delivering non‑personal data to Users… without making money

Each User of a Musko or connected device (not only natural persons like you, but legal entities such as the dealership) has the right to receive data generated by their Muskos. Personal and non‑personal.

And to receive such data easily, free of charge, and securely. In structured, machine‑readable format.

How? In accordance with the terms laid out in that contract that Muskolini must present to its users, terms that must respect the limitations imposed by the Data Act.

Muskolini may limit and regulate the use of the data — non‑personal — being transferred subject to certain limits.

And it may charge business users for providing that data, but not individual consumers. That has its own nuance too.

Meanwhile, the dealership that buys Muskos to rent (being a User vis‑à‑vis Muskolini) is, as Data Holder, subject to data requests from its lessee Users.

But… Can they do what they want with the non‑personal data from my gadgets?

This matter is complex and will produce rivers of ink. There are multiple pre‑delivery and post‑delivery limitations. Here just a couple of things.

Fun fact: A User that happens to be a competing company of the Data Holder may not directly request data from a connected product and use it to develop a competing product…

But… do you know what you can do?

An organization may convince or incentivize individual users to exercise their rights, obtain usage data from those gadgets… and transfer it to them.

Think of the opportunities for consumer associations, price comparison services, product reviewers… and academia.

This option is barred for designated “Gatekeepers” under the DMA.

GDPR prevails over the Data Act and the Data Act… isn’t itself a legal basis under the Data Act

One of the great gems of this regulation is that:

The Data Act explicitly declares itself subject to the supremacy of the GDPR, and then

Recognizes that the Data Act itself does not constitute a legal basis for the transfer of personal data.

That is: I drive a Musko and take my daughter’s best friend on a trip. I pick her up from school because there’s a great charging station.

Well:

I can request the data — generally non‑personal — on connection, charging, and consumption (whatever is available) from Iberdrola or whoever provides the charging service.

I can request the data — generally non‑personal — on connection, charging, and consumption (if available) from the commercial provider of the app handling the charging and payment, if I use one.

And here’s the real juicy part:

I — as User (Data Act) and Data Subject (GDPR) — can request my personal data captured by the Musko (and that of my daughter, on her behalf).

It´s relevant data: your Musko (and Muskolini) knows where you live, where you work, if you go to expensive or cheap places to eat and on vacation, if you travel too much for work and live a shitty life, if you’re a good driver or a Fernando Alonso, if you stay in hotels midweek for “third phase encounters”.

Muskolini must provide me with my non‑personal data in accordance with the contract signed with me as User, or otherwise, my personal data under my legal right of access as a Data Subject.

You’ll need a much larger legal basis

And here the familiar “usual” certainties run out and we need to resort to “weird” solutions (curiously: our specialty).

In the examples below, the Data Holder (Muskolini and/or the rental company) will have the responsibility to:

Assess whether there is sufficient legal basis from the User‑Data Subject or Non‑User Data Subject requesting access to their (or third‑party´s) personal data.

Not to mention ensuring the identity of those individuals without messing up.

For instance:

My daughter’s best friend (or legal representative, her parents) may request her personal data captured by my Musko:

From Muskolini (if I bought the car), or

From the dealership (if I rented it), or

From me, if I obtained it from any of the above.

Because the User exercising the Act‑ccess right over personal data (or non‑personal data that, in their hands, becomes personal) becomes a “Controller” under the GDPR — except for domestic exceptions — and a “Holder,” under the Data Act.

Same applies to all children entering or leaving the school and captured by the Musko’s cameras or sensors.

Same applies to any passersby captured by the Musko, whether stationary or in motion.

Controller, co‑controller, processor

If the Musko is rented, both the User and the Non‑User Data Subject will have to approach separately each of the Data Holders (Muskolini as manufacturer and the dealership as rental company) to claim their data.

Typically, a manufacturer, to avoid trouble, will subcontract to a third party all the platform work for channeling the delivery (and sale) of data.

Needless to say, distinguishing between controller, joint controller, and processor will not be straightforward…

…especially if someone reserves AI‑training or similar capabilities for its own purposes.

It’s not risky to predict that, until complaints and fines begin, everyone will pose as mere processors invoking the usual delulu arguments.

The Scania doctrine

On September 4 we will learn the CJEU ruling in the EDPS vs SRB case that inaugurated three years ago the “subjective interpretation” of personal data and crystallized into the “Scania doctrine” in cases like Scania or IAB Europe.

We do not expect fundamental surprises, beyond reaffirming what has already been declared repeatedly. Although we wouldn’t be surprised if it throws a lifeline to the EDPS.

The Scania doctrine, once processed by the common people, will change how both GDPR and the Data Act are applied.

I’ve left 99 % of things unmentioned but…

…that’s enough for today

These are only a few of the two hundred derivatives resulting from the Data Act.

Expect more posts like this, because the topic is rich‑rich and the issues and wit come naturally.

If this topic squeezes you and you need help, reach out!

Also, in early September we will offer specific training with the aforementioned Sergi Ariño — who has been turning this over for much longer than I have.

Have a great weekend and back to work.

Jorge García Herrero

Lawyer and DPO